Key Takeaways

- Decision-grade benchmarks must be relevant, timely, consistent, and interpretable — not just statistically correct.

- When confidence depends on time-consuming research and reconciliation, the benchmark itself usually isn’t strong enough.

- The real test isn’t whether a comparison looks right today, but whether it can be defended when decisions are questioned later.

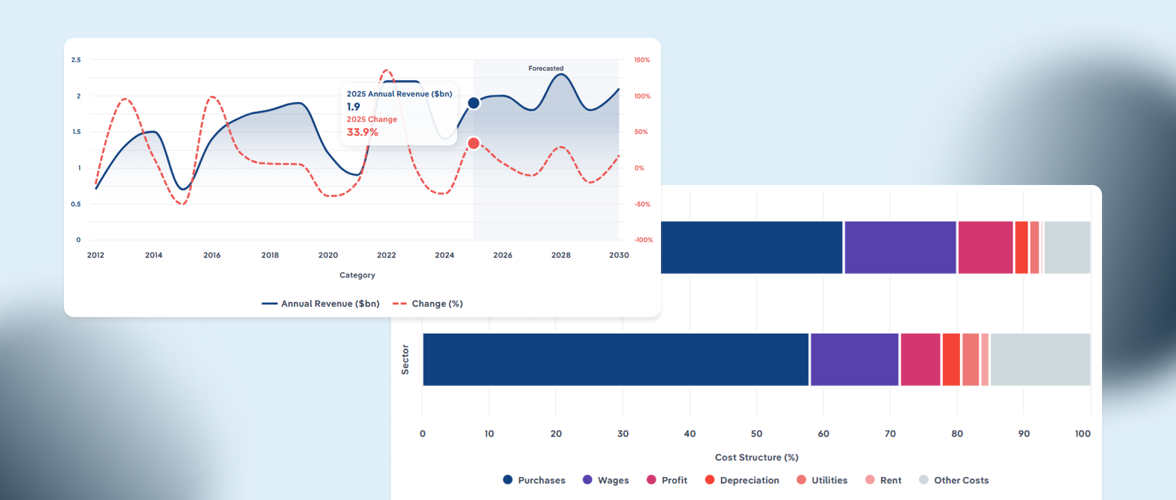

Most business decisions rely on industry benchmarks.

They sit quietly in the background of meetings and models, shaping how leaders interpret performance, assess risk, and decide whether something is “normal,” “concerning,” or “exceptional.”

Revenue growth is judged against industry reference points. Costs are evaluated relative to peer performance comparisons. Risk is framed using sector-level context.

Rarely does anyone pause to ask a more basic question: are these benchmarks actually trustworthy enough to make decisions with?

In many organisations, industry context is still assembled manually. Analysts search across disconnected sources. Figures are copied into spreadsheets, slides, and models. Assumptions are reused because revalidating them would take too long. Multiple versions of the “same” benchmark circulate, close enough to be useful but never authoritative enough to replace the rest.

The result is a contradiction most teams recognise instinctively: decisions that feel data-driven, built on foundations that feel surprisingly fragile.

Industry benchmarks are treated as objective truth that stabilise judgement. If the numbers are calculated correctly and sourced from somewhere reputable, they are assumed to be fit for purpose.

That assumption is rarely challenged.

And when it should be, the consequences don’t announce themselves immediately. They surface later as hesitation, rework, and a lingering sense that the confidence behind a decision required more effort than it should have.

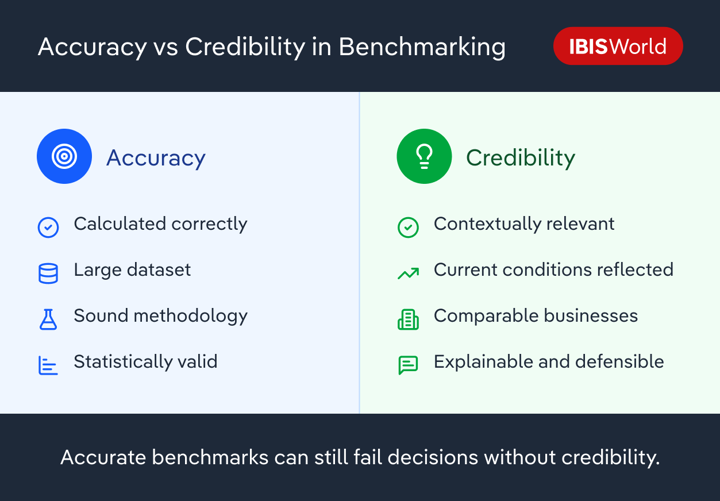

Why does accuracy alone not make a benchmark credible?

It’s easy to assume that accuracy and credibility are the same thing. They’re not.

An industry benchmark can be calculated perfectly and still mislead the people using it. The dataset can be large. The methodology defensible. The comparison technically sound.

And yet the decision it informs can still be wrong.

Accuracy answers a narrow question: Was this calculated correctly?

Credibility answers a harder one: Should this influence a real decision under uncertainty?

Most benchmarking failures live in the gap between those two questions.

Industry averages, when used in isolation, are a good example. They compress wide variation into a single industry performance baseline that feels stable and authoritative. That stability is comforting. It’s also misleading. Averages flatten risk, obscure dispersion, and hide the differences that often matter most.

The more complex the industry, the more dangerous that compression becomes.

There’s also a psychological effect at play. Precision creates confidence. Clean charts and decimal points signal rigor, even when the underlying comparison is weak. Over time, that presentation carries more weight in decision-making than the benchmark itself deserves.

Many industry benchmarks are accurate in isolation but fragile in context. They hold up as reference material but break down when used to justify choices that carry real consequences.

That fragility rarely shows up immediately. It appears later, when outcomes diverge from expectations and leaders struggle to explain why something that “looked fine on paper” didn’t hold up in reality.

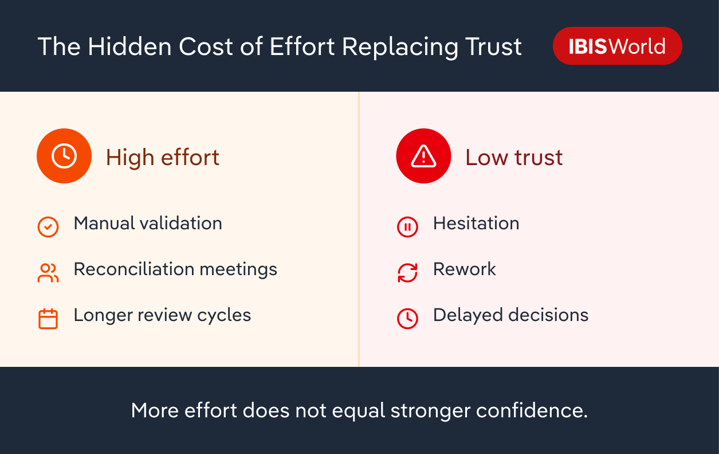

When effort becomes a substitute for trust

Few organisations choose weak industry context deliberately.

More often, they drift there. Manual research fills gaps when reliable comparisons are hard to find. Estimates are reused when sourcing fresh data feels too slow. Multiple sources are combined to compensate for uncertainty, even when those sources conflict or lag.

Over time, something subtle shifts: effort becomes a proxy for confidence.

If an analysis took days to assemble, it feels more trustworthy. If several datasets were reconciled by hand, the output feels safer even if the underlying signal remains unstable. The work looks rigorous, but the foundation hasn’t changed.

This creates a hidden cost that rarely appears in reports.

Teams spend more time validating inputs than interpreting outcomes. Meetings focus on reconciling numbers instead of understanding implications. Decision-makers receive polished outputs, yet hesitate — sensing that something underneath is less solid than it appears.

Unreliable industry context doesn’t just slow work down. It erodes trust in the work itself.

And when trust erodes, organisations respond predictably: more review, more process, more manual effort. The behaviours meant to create confidence end up reinforcing the original problem.

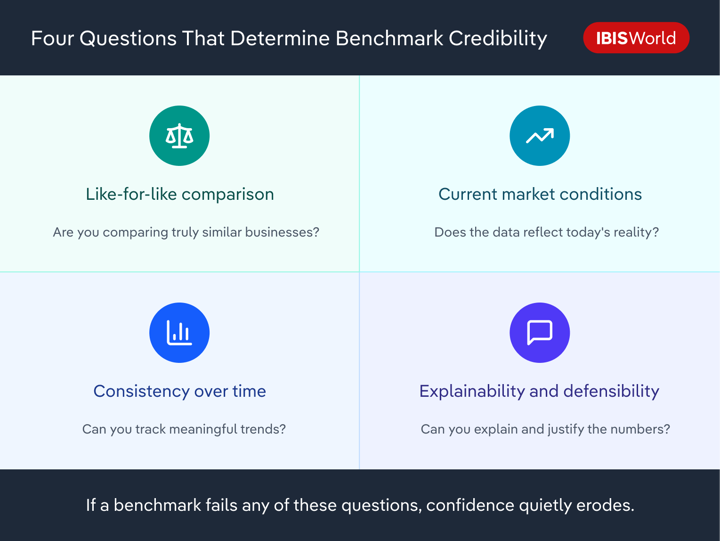

Four questions that quietly determine benchmark credibility

Most leaders already know when a benchmark feels weak, even if they can’t articulate why.

In practice, credible industry benchmarks tend to survive four questions. They’re rarely asked explicitly, but they shape whether a comparison is trusted or quietly worked around.

Are we really comparing like with like?

Industries aren’t uniform. Size, operating model, geography, customer mix, and maturity all matter. When those differences are collapsed into a single category, the benchmark may describe an industry in name, but not in substance.

That’s why discomfort often lingers even when a peer comparison is statistically sound. The numbers align. The businesses don’t.

Does this reflect where conditions are now — or where they were?

Most industry benchmarks are backward-looking by design. In stable environments, that lag may be tolerable. In volatile ones, it distorts judgement.

Can we trust this trend over time?

Benchmarks are rebuilt as industries evolve. Methodologically sound changes can still break continuity, turning apparent shifts in performance into artefacts of construction.

Can we explain why this looks the way it does?

A benchmark that can’t be explained can’t be defended. When numbers become black boxes, confidence becomes brittle.

Why lag changes how decisions feel — not just what they show

When industry benchmarks fail, it’s rarely because they’re wrong. More often, they’re late.

Lag is easy to rationalise. Data takes time to collect, validate, and aggregate. By the time a benchmark is published, it’s usually correct — just no longer current.

The problem is how those lagged benchmarks are used.

They’re treated as real-time signals, even though they describe a past state of the world. Deterioration looks acceptable because peers “look similar.” Emerging opportunity looks premature because the benchmark hasn’t caught up yet.

Volatility exposes this quickly. Leaders sense change before the numbers reflect it. Confidence erodes, decisions slow and debate replaces action.

That’s how lag becomes more than just a reporting inconvenience. It becomes a credibility problem.

When simplification starts working against understanding

Simplification isn’t the enemy. Without it, benchmarks become unusable. But simplification always removes something.

To make benchmarks easier to consume, variance, nuance, and edge cases are stripped away. What remains is clean and intuitive — and often incomplete. Early warning signals, usually visible in ranges rather than averages, disappear first.

Over time, simplified reference points harden into benchmarks that are defended rather than examined. They become familiar. Comfortable. Hard to challenge.

At that point, simplification doesn’t just obscure reality. It resists correction.

Credible industry benchmarks manage complexity rather than eliminating it. They preserve enough structure to support interpretation, even if that makes conclusions less tidy.

When a comparison feels unusually easy to accept, that’s often a signal to slow down, not move on.

Why judgement still matters

Benchmarks don’t make decisions. People do.

Formulas can calculate comparisons, but they can’t determine whether those comparisons make sense in context. They can’t recognise structural differences, account for recent change, or explain why a result feels intuitively wrong.

Human judgement fills those gaps. Experienced decision-makers test benchmarks mentally. They ask what might be missing, what assumptions are embedded, and what would need to be true for the comparison to hold.

That interpretive layer isn’t bias. It’s quality control.

Credible benchmarks are designed to work with judgement, not replace it. But this is where many organisations find themselves stuck.

They know judgement matters. They know benchmarks are imperfect. And yet, they still rely on processes that make confidence expensive — requiring manual research, reconciliation, and repeated interpretation just to reach a defensible view.

At that point, the question is no longer just whether a benchmark is credible, but whether the way it is being used can scale with the decisions it is meant to support.

Final Word

Benchmark credibility is often treated as a technical concern. In reality, it’s a leadership issue.

Industry benchmarks shape how organisations interpret performance, justify decisions, and explain outcomes. When they’re credible, they accelerate judgement and reinforce confidence. When they’re not, they quietly distort priorities and erode trust.

The risk isn’t just a bad decision. It’s the gradual acceptance of shallow explanations for complex outcomes.

The most important question, then, isn’t whether a benchmark is accurate. It’s whether it’s worthy of the decision it’s being used to support.

That question can’t be delegated. And it deserves far more attention than it usually gets.