Key Takeaways

- Decision confidence weakens when interpretation breaks down, not when performance immediately deteriorates.

- Early doubt reflects stress in assumptions, context, or explanatory logic rather than visible failure.

- Organisations that wait for results to change often miss the most controllable moment to act.

When confidence fades, it is often treated as a reaction to results.

A soft signal. A feeling. A loss of nerve that should be ignored until the numbers say otherwise.

That framing is convenient and usually wrong.

In practice, confidence tends to weaken before performance changes, not after. Not because leaders are irrational, but because they are responding to something results have not yet captured.

What erodes first is not outcomes, but the ability to clearly explain why a decision still makes sense.

The gap between outcomes and understanding

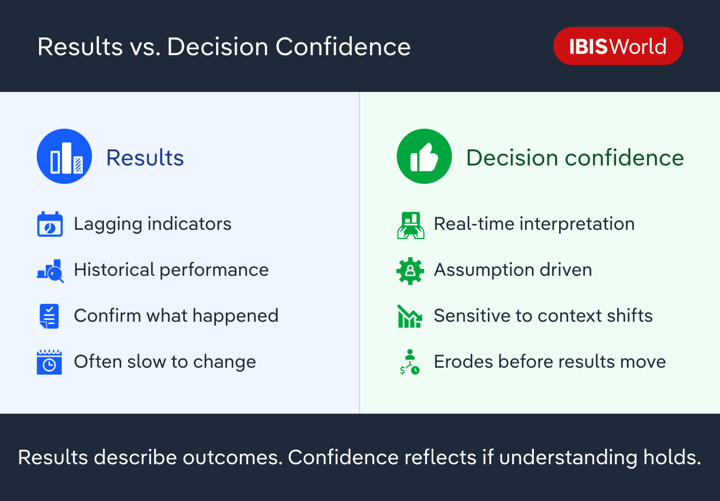

Performance metrics answer a narrow question: what happened?

Confidence answers a broader one: does our understanding still hold?

That distinction explains why the two rarely move in sync. Results are cumulative and delayed. Confidence is immediate and interpretive. It responds to shifts in conditions, assumptions, and context long before those shifts appear in reported performance.

When leaders begin to hesitate, it is rarely because numbers have turned. It is because the logic connecting decisions to outcomes has started to feel strained.

When decisions become harder to stand behind

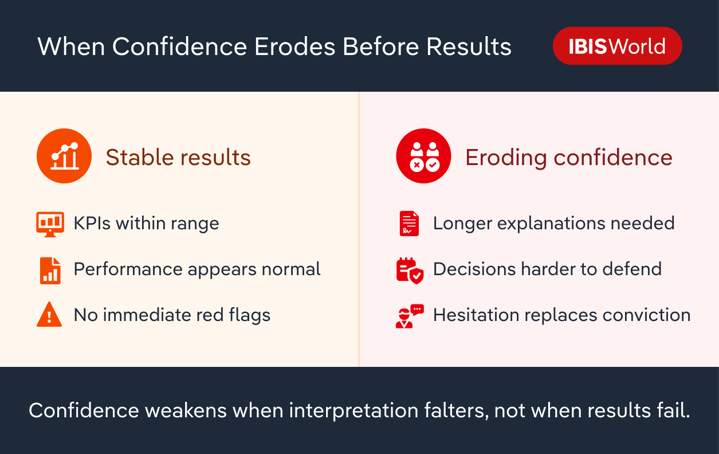

One of the clearest signs of eroding confidence is not declining performance, but defensive reasoning.

Decisions that once required little explanation now demand careful qualification. Leaders spend more time clarifying intent, restating assumptions, and reassuring stakeholders that nothing fundamental has changed.

The decision itself may be unchanged. The confidence behind it is thinner.

This is not caution for its own sake. It is an intuitive response to growing uncertainty about whether current results are still representative of underlying conditions.

Why stability can be misleading

Stable results are often interpreted as proof that a decision remains sound.

In reality, stability can mask divergence.

Markets adjust unevenly. Costs, demand, and risk rarely move at the same pace. By the time results clearly reflect deterioration, the conditions that produced them have often already shifted.

Confidence erodes during this gap.

Not because outcomes are bad, but because leaders can no longer tell whether outcomes are durable.

The role of context in early doubt

Early doubt rarely originates in the data itself.

It emerges when results lose their reference point.

Without credible external context, decision-makers struggle to answer basic interpretive questions:

- Is this performance strong given current conditions?

- Is this outcome being sustained by temporary tailwinds?

- Are peers seeing the same patterns, or something different?

When those questions lack clear answers, confidence weakens, even if the numbers look fine.

How organisations misread the signal

Most organisations are trained to treat confidence as subjective and results as objective.

So when the two diverge, confidence is discounted.

Leaders are told to wait. To avoid overreacting. To let the data “settle.”

What gets missed is that confidence erosion is often the first visible indicator that interpretation has broken down. Waiting for results to confirm it simply delays the response.

By the time outcomes move decisively, the opportunity to adjust cheaply has usually passed.

What early confidence erosion actually signals

Confidence erosion is not a verdict. It is a diagnostic.

It suggests that:

- Assumptions may no longer align with conditions.

- Context may be outdated or incomplete.

- Explanations no longer travel well across the organisation.

These are structural issues, not emotional ones.

Treating them as noise allows them to compound.

Why restoring confidence is not about reassurance

Confidence does not return because leaders are told to “stay the course.”

It returns when interpretation becomes coherent again.

That coherence comes from updated context, clearer external reference points, and renewed clarity about what current results actually imply.

When decision-makers can once again explain why outcomes look the way they do, hesitation fades, even before performance changes.

When confidence becomes a leading indicator

Organisations that pay attention to confidence erosion respond earlier.

They revisit assumptions before outcomes force the issue. They ask whether context has shifted. They recalibrate while optionality still exists.

In those environments, confidence is treated as information, not sentiment.

It becomes a leading indicator of decision quality rather than a casualty of results.

Final Word

Results describe the past.

Confidence reveals whether understanding is keeping pace with the present.

When confidence erodes before results do, it is rarely a failure of discipline or resolve. It is an early warning that interpretation needs attention.

The organisations that recognise that moment tend to adapt sooner — and with far less disruption — than those who wait for performance to deteriorate visibly.

By the time results make the problem undeniable, the cost of ignoring early doubt is usually far higher than the cost of addressing it when it first appeared.