Key Takeaways

- The biggest AI impact isn’t in tech roles. It’s hidden inside administrative, financial, and professional services work where skill overlap with AI is far greater than most leaders realise.

- Early-career work is the real pressure point. The tasks that once trained the next generation are often the same tasks AI now performs best, putting long-term capability at risk.

- AI doesn’t replace organisations, it amplifies them. Firms that treat skills, data, and learning as strategic assets will compound the upside, while others quietly multiply inefficiency and talent gaps.

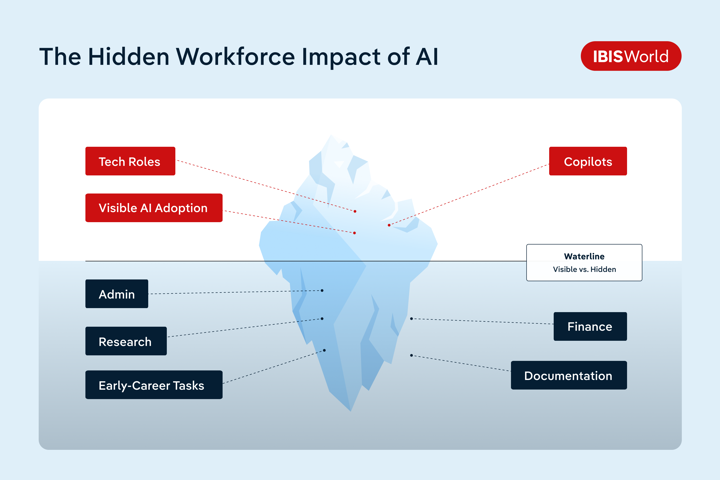

Most leaders believe they know where AI will disrupt their organisation. They are almost certainly looking in the wrong place.

The real impact of AI is not showing up in job titles, org charts, or innovation labs. It is emerging quietly inside the everyday work that keeps firms running: analysis, documentation, coordination, and first-pass thinking. Work that rarely makes headlines, but carries a significant share of wage value.

I see this gap often. We talk about AI in terms of roles and tools, while the economics of work are shifting underneath us. But the real silent impact is where the skills are eroding.

Most conversations about AI and work still revolve around jobs. Which roles are at risk. Which functions will change. Last year, when MIT released its Project Iceberg report, it deliberately steps away from that framing and asks a more useful question: where does economic value sit and how much of that value is now technically within AI’s reach?

Instead of analysing job titles, the researchers model skills, mapping wage value to tasks AI systems can already perform today. That shift matters. Jobs are abstractions. Skills are not.

Viewed this way, the findings are clear. AI exposure in technology roles exists, but it is relatively small and highly visible. The much larger impact sits elsewhere, embedded in administrative, financial, and professional services work. Not concentrated in tech hubs, but spread across firms and functions that rarely feature in AI headlines.

The warning sign leaders should not ignore: early-career work

One part of the Project Iceberg analysis deserves far more attention from business leaders: early-career roles.

The data shows a clear pattern. In occupations with higher AI exposure, employment among 22–25 year olds is declining faster than in less exposed roles. At the same time, job postings in those same fields are shifting away from entry-level positions and toward more experienced hires.

This is not a theoretical future risk. It is already showing up in hiring behaviour.

For many professional services firms, this should feel uncomfortably familiar. The tasks that have traditionally made up the first rung of the career ladder are often the same tasks AI systems now handle well: first-pass analysis, document preparation, standardised research, and routine synthesis.

When those tasks quietly disappear, so does the training ground where context, judgement, and craft are passed from one generation to the next.

Early-career roles have always been about more than output. If AI absorbs that work and organisations do not actively redesign junior roles, the result is not just efficiency gains. It is a hollowing-out of future leaders.

I know that's where I got my experience, and my years of judgement to help me make the decisions today. What happens to our leadership pipeline? How do we plan for the future of our talent?

This is where short-term optimisation collides with long-term potential. Reducing low-value work feels rational. But if the work you remove is also how people learn, you risk creating teams that look productive on paper but struggle to develop depth of talent over time.

This is not an argument against using AI in early-career workflows. It is an argument for being deliberate. AI should compress the time it takes for someone to become excellent, not eliminate the experiences that make excellence possible.

Firms that get this wrong may not notice immediately. The impact shows up years later, when there is a gap where mid-level judgement should be, and no obvious way to fill it. That is why the early-career signal in Project Iceberg matters so much. It forces a harder question than cost or productivity: what kind of professionals are we actually building in an AI-enabled organisation?

Why “jobs at risk” is the wrong way to think about AI

One of the most valuable aspects of Project Iceberg is what it does not claim.

It does not attempt to predict how many jobs will disappear or which titles will be obsolete. Those forecasts may grab attention, but they rarely help leaders make better decisions inside their own organisations.

Instead, the Iceberg Index focuses on overlap. It measures where the skills that generate wage value today intersect with what AI systems can already do. Not in theory. Not in a distant future. Now.

Overlap is not the same as replacement. High overlap does not mean a role vanishes. It means the composition of work inside that role is unstable.

I often think of it as an earthquake risk map. It does not tell you when disruption will happen. It shows you where the ground is most likely to shift, so you can decide how to build.

For executives, this framing is far more useful. It moves the conversation away from defensive questions about headcount and toward design questions about work. Which skills still require human judgement. Which tasks can be automated or augmented. Where time and attention should be reallocated as technology improves.

What this means when you are actually running a business

National indices are useful, but the real work begins when leaders translate those signals into decisions about teams, workflows, and products.

From where I sit, the most important lesson from is this: AI does not respect organisational charts. It operates at the level of skills and tasks.

That has three practical implications.

Shift the focus from jobs to skills

Jobs are bundles of activities. Some are judgement-heavy and deeply human. Others are repetitive, structured, and increasingly well suited to AI assistance.

Understanding real exposure requires visibility into the skills embedded in high-cost, high-volume functions such as finance, accounting, research, customer operations, and compliance. Not as role descriptions, but as the work people actually do week to week.

Once you take that view, patterns emerge quickly. Where AI can take on the heavy lifting. Where humans add disproportionate value. Where time is spent simply because “that’s how it’s always been done”. That is where your own iceberg lives.

Treat data quality as a workforce strategy

One of the quieter signals in the Iceberg findings is where AI exposure concentrates. Not in areas with pristine data, but in functions built on templates, documents, taxonomies, and institutional knowledge.

In those environments, the limiting factor is rarely the model. It is the data.

Inconsistent structures, siloed systems, and brittle processes all reduce how much value AI can realistically deliver

The early-career signal in Project Iceberg makes one thing clear: doing nothing is still a decision.

If AI absorbs entry-level tasks and firms do not rethink how junior roles are structured, learning opportunities disappear by default. Leaders need to be explicit about what early-career roles are for in an AI-enabled organisation.

That means shifting people toward review, judgement, and context earlier. Pairing AI-driven workflows with intentional learning paths. Tracking not just productivity, but the skills new joiners are actually building.

AI should raise the floor and accelerate growth. If it quietly removes the ladder, the long-term cost will outweigh any short-term efficiency gains.

Taken together, these shifts point to a broader truth. AI strategy is no longer just about tools or pilots. It is about how work itself is designed.

How to find your own iceberg

Start small. Choose a few functions where labour costs are meaningful and work is relatively standardised. Financial reporting, tax, customer operations.

Map tasks rather than roles. List the core activities, how often they occur, how long they take, and the wage cost attached. This step alone often surfaces more insight than any technology review.

Then assess AI exposure bluntly. Not what might be possible someday, but what is realistic now:

- AI is not useful yet

- AI can assist meaningfully

- AI can handle most of the heavy lifting with human review

When teams are honest, the iceberg appears quickly. Large portions of time and cost sit in work already overlapping with existing tools.

The final step matters most: respond by design, not drift.

For high-exposure tasks, leaders have real choices. Automate and reallocate time. Redesign workflows so AI produces a first draft and humans focus on judgement and context. Adjust roles and training so skills evolve alongside the tools.

An internal Iceberg review is not about predicting job loss. It is about taking responsibility for how value is created as AI capabilities accelerate.

Final Word

AI is not a reset button. It is a multiplier.

In organisations with messy data, brittle workflows, and outdated role design, AI will amplify those weaknesses. In organisations that treat skills as the unit of design, invest in strong data foundations, and take talent development seriously, AI does the opposite.

The difference is not the technology. It is leadership intent.

Waiting for external benchmarks to dictate action is a mistake. By the time job loss is visible in the data, the most important design decisions have already been made.

The better approach is to look inward early. Identify where your iceberg sits. Be honest about overlap between human effort and what AI can already do. Then make deliberate choices about how work, data, and learning evolve together.

Start small. One function. One workflow. One set of skills.

But start on purpose.

AI doesn’t replace organisations. It amplifies them.

Messy data, weak workflows, or hollow skill ladders — AI makes those problems louder.

But strong data foundations, smart task design, and deliberate learning paths? AI compounds those too.

Start small.

Map your own iceberg — the overlap between what humans do and what AI already can.

Then act on purpose, not panic.

AI isn’t the reset button. It’s the multiplier.