Key Takeaways

- AI threatens to deepen existing inequalities as urban hubs thrive while regions like the West Midlands lag behind, heightening wage gaps and job challenges for young graduates in urban centres.

- Upskilling is vital for resilience in today’s evolving job market with 39 percent of core skills expected to change by 2030 and future skillsets increasingly emphasising creativity and socio-emotional intelligence.

- Global AI oversight must rise above borders to ensure responsible innovation through international collaboration between governments and companies to address ethical dilemmas, rebuild public trust and create resilient labour markets.

AI marks the latest stage in a long continuum of technological disruption that’s reshaped how societies organise and value work. From the agricultural revolution to the digital economy, each major innovation has redefined productivity, employment structures and the relative worth of human skills. The rapid uptake of AI since 2023 signals a new era of work defined by a new general-purpose technology (GPT). GPTs, like electricity or the internet, have a widespread and transformative impact across the economy. While AI’s stance as a GPT remains debated, mounting evidence suggests it has the potential to transform not only the nature of tasks but also the organisational and institutional frameworks governing labour markets.

While technological progress has historically driven economic growth and improved living standards, it often exacerbates inequality, particularly when skill requirements shift more rapidly than workers can adapt. The UK faces this dual challenge: leveraging AI to increase efficiency and boost economic growth, while preventing new divides between high-skill, high-income sectors and those vulnerable to automation.

So far, AI adoption in the UK remains fragmented across industries, regions and occupations. Large companies have more readily adopted AI, with roles in marketing, sales, technology and professional services the most affected. Projections suggest that the most immediate productivity gains (and labour disruptions) will stem from software capable of automating cognitive and administrative functions, rather than the much costlier physical AI-powered robotics.

Uncertainty remains regarding the scale and timeline of labour transformation, creation and displacement. Questions around how AI will impact data governance, ethical design, inequality, re-skilling and human oversight will take centre stage for policymakers, companies and workers navigating the change.

Productivity and work in the age of AI

Productivity is one of the key promises of AI. Yet it’s uncertain if it will deliver.

Optimistically, AI could bring the long-anticipated hike in leisure time that previous technological revolutions have failed to offer. If employers can automate complex cognitive and even physical tasks for a relatively low cost, they may be able to pay employees more for fewer hours of more effective work, without impacting the bottom line. An increase in leisure time would lead to higher spending, boosting the economy across the board.

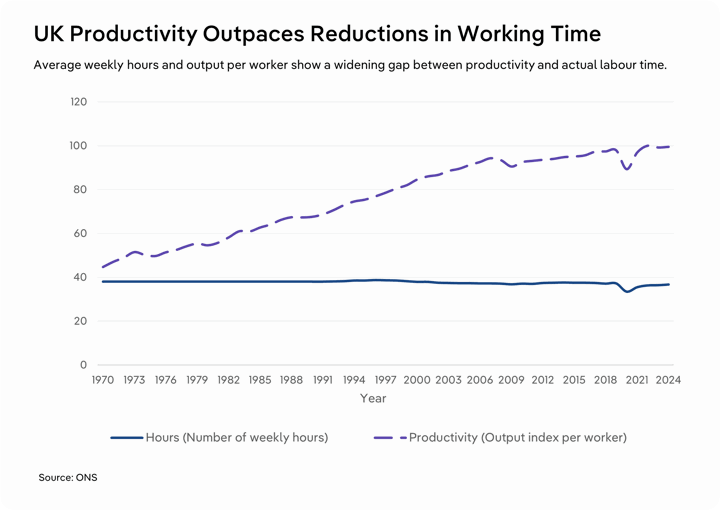

This has happened in the past. During the three decades following World War II, strong collective bargaining and tighter labour market regulation led to a steady drop in the average full-time workweek in the UK, from 46 hours in 1946 to just under 40 hours in 1979. The UK would have been on target to reach a 30-hour week (equivalent to a 4-day week) by 2040, had hours continued to fall in line with the initial post-war trend. However, from 1980, this trend faltered with the deregulation of the labour market, resulting in a dip of just 1.3 hours to 36.7 hours in 2024.

A more conservative outlook might be that even if productivity rises with the widespread adoption of AI, work hours will remain largely the same. This outlook seems plausible, particularly as any significant productivity gains remain elusive as of 2025. Without strong collective bargaining from workers and tighter labour market regulation, any gains in productivity are likely to widen inequality rather than boost economic growth.

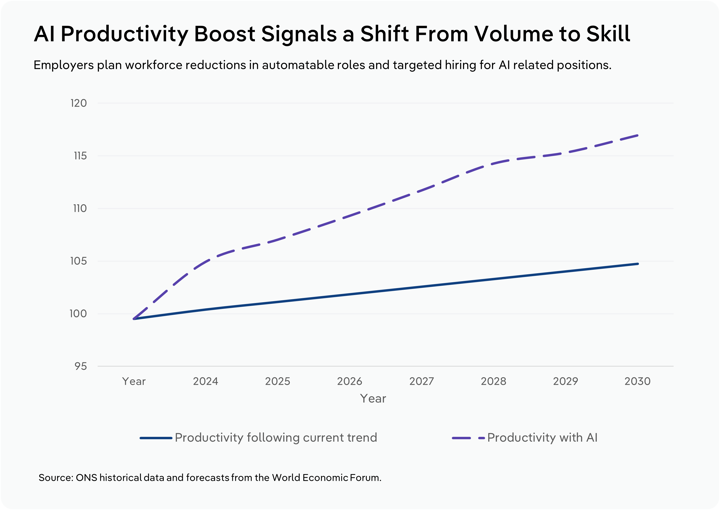

Largely in line with these productivity expectations, 40% of the largest global employers plan to reduce their workforce where AI can automate tasks by 2030. Three-quarters of these employers also plan to hire for new AI-related jobs during the same period, but they expect their wage costs to remain largely unchanged. This suggests that many lower-skill jobs are set to be replaced by fewer, higher-skill jobs.

Uneven adoption and uneven results across companies

AI is likely to increase global and regional wealth disparities, as AI-driven businesses will be the core beneficiaries of this technology. AI might displace human workers in many fields. While AI could create new jobs, the total balance remains uncertain. For example, the World Economic Forum expects global employment to expand by 7% between 2025 and 2030, with some of the fastest-growing roles driven by technological developments like AI and robotics. Figure III illustrates which jobs are the fastest-growing and fastest-falling.

AI has the potential to widen the gap between large and small companies. Large companies are expected to benefit the most from AI productivity gains, while smaller companies could see only modest results. This is mainly because larger companies have more capital to invest and more proprietary data to train bespoke Large Language Models (LLM) on. These tailor-made LLMs are set to be more efficient than off-the-shelf AI products available to smaller companies. Since SMEs represent over 99% of UK businesses, this might also reduce the impact of AI adoption on the UK labour market. Notably, although 35% of SMEs in the UK reported using AI in 2024, only 11% reported using AI to a significant degree to automate or streamline their operations.

Widening geographic and demographic gaps

Geographically, AI could widen existing disparities. New AI-driven jobs will likely be created in areas that already concentrate high income and investment. For example, the US hosts more than 40% of global AI companies and startups, while the UK hosts 7%. Domestically, London houses three-quarters of AI companies. This is because R&D, infrastructure and investment are already highly concentrated around urban innovation hubs.

This increases the risk that already disadvantaged groups in other regions of the country may fall further behind. Currently, average wages in London are about 27.8% higher than in the West Midlands, the region with the lowest median weekly income. This is largely the result of a high concentration of high-paying jobs and highly-skilled professionals (who tend to work in better-performing labour markets) in the capital. As the fastest-growing jobs are expected to be concentrated in London and other major cities, wage disparities may expand.

Another key geographical trend is that young Britons are disproportionately concentrated in cities. Some of the youngest cities include London, Bristol, Manchester, Glasgow, Edinburgh and Leeds. Since AI is expected to disrupt entry-level jobs the fastest – with junior positions already falling by 5.8% between 2021 and 2025 – AI adoption could severely constrain the work prospects of young graduates, particularly in these regions.

Mixed impact on job creation

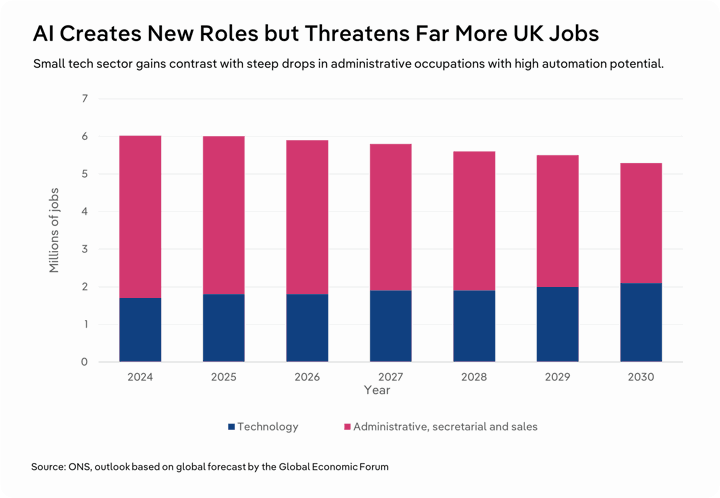

While some AI-driven jobs are expected to nearly double over the next five years, the UK tech sector employs only 1.7 million people, which is approximately 7.9% of all jobs in the UK. Approximately 20% of Britons are employed in administrative and secretarial occupations and sales and customer services, which are among the fastest-declining jobs as a result of AI and automation. In addition, 25.7% of people are employed in professional occupations, which are mainly knowledge-work-based but could also be automated (to some degree) in the coming years.

The UK could lose a significant amount of crucial jobs outside of urban areas, where tech companies and jobs are concentrated. Research also suggests that AI may widen the gender and ethnic gaps in the labour market by exacerbating implicit discrimination in the recruitment process, limiting work opportunities for disadvantaged groups. This is a commonly discussed topic regarding the use of AI in hiring and other HR tasks, as the data used to train LLMs will inevitably reflect the existing inequalities and biases that human recruiters have exhibited. Bias in AI models can also arise from algorithmic design flaws and subjective human decisions made during the development process.

Without intervention, these widening inequalities threaten economic stability, social cohesion and the country's long-term growth potential. However, mitigation strategies to limit AI’s bias remain experimental and lack empirical validation, so continued evaluation of these strategies and AI’s application in hiring is necessary.

Retraining and re-skilling for AI-supported work

As AI transforms the nature of work, re-skilling and training will become fundamental challenges. Creative thinking and socio-emotional attitudes will become increasingly important skills; resilience, flexibility, curiosity and interest in learning are becoming more important for employers. Major global employers expect 39% of workers’ core skills to change between 2025 and 2030.

While most workers exposed to AI may not require specialised AI technical skills, organisations are increasingly seeking professionals capable of managing and interpreting AI systems effectively. Employers are also seeing the need to be flexible and support their employees in response to these technological developments, as learning programmes are, in many cases, more cost-effective than hiring new employees. An estimated 38% of UK organisations are prioritising AI upskilling in 2025.

It's also worth mentioning that disruption to skills is not uniform across industries or countries. Generally, higher-income economies are more stable in their labour needs. Still, in more developed economies, AI has the potential to improve the supply of labour by increasing the quantity and quality of workers in the economy, which can help create a more resilient labour force and market. Research suggests that AI could raise UK students’ educational attainment over their academic career by 6%. Emerging evidence also indicates that lower-performing students are likely to experience the greatest gains from AI-enabled education, highlighting AI’s potential as a social levelling tool.

Governance and collaboration

Governance and collaboration will be the key to successfully navigating the changes to the labour market as AI use grows. Policymakers will need to take a strong and clear stance on the risks of AI.

The EU’s AI Act, adopted in June 2024, is the world’s first AI regulation. Although its adoption is ongoing, it aims to ensure that AI systems used in the EU are safe, transparent, traceable, non-discriminatory and environmentally friendly.

The EU concluded that AI systems should be overseen by people, rather than by automation, and drew a hard line against AI applications that pose an unacceptable risk to humanity. These include AI use for biometric identification, cognitive manipulation and social scoring, which were banned on 2 February 2025.

On the theme of collaboration, the EU AI Act aims to support companies, particularly SMEs, in testing AI systems in controlled environments that simulate real-world conditions, helping them compete in the growing AI market without compromising the EU’s safety targets.

Industry leaders will need to adopt an approach that reconciles AI’s alignment with the broader organisational strategy, while also prioritising regulatory compliance. Organisations should also establish systems that enable employees to experiment with AI tools and incentivise the cooperative development of these tools.

Initiatives like the UK’s AI Skills Boost are putting the UK on the right track for responsible collaboration. Jointly identifying future skill needs and focusing on how industry and government can work together to keep workers’ skills relevant will be key to maintaining the resilience of the British labour market.

Final Word

When thinking about the future of work with AI, it’s essential to recognise that AI is constantly evolving. The strides in LLM development seen in the last two years show that, whether it is automating tasks or collaborating with humans, AI is reshaping work faster and more thoroughly than any technology before.

In the future that AI companies seem to be heading towards, people will no longer interact with AI models by asking questions or by having them generate visual content. Instead, AI “agents” will perform tasks largely without human supervision. People will give complex tasks to “reasoning models” that work through tasks logically (but require 43 times more energy than a regular query), “deep research” models that spend hours creating research reports or “personalised” AI models trained on a single person’s data, knowledge and preferences.

This future is around the corner. OpenAI will reportedly offer AI agents for USD $20,000 per month and will use reasoning capabilities in all of its models going forward. DeepSeek is catapulting “chain of thought” reasoning into the mainstream with a model capable of generating around nine pages of text for a single response.

Regulations and other government responses should ideally target the future capabilities of AI systems. For example, Dario Amodei, Anthropic’s chief executive, stated in a US Senate hearing that in a few years, AI models will be able to provide all the information to build bioweapons. Gary Gensler, the chairman of America’s Securities and Exchange Commission, predicted that an AI-generated financial crisis was nearly unavoidable without swift intervention. While these are more extreme, generalised risks, similar existential threats are set to challenge private and public organisations.

To stay ahead of these challenges, it is crucial for companies and the government to come together in regulating AI use and development and fostering a resilient labour market to protect jobs and workers. Countries can improve the resilience of their labour markets by emphasising comprehensive social safety nets, universal access to education, re-skilling projects and stable economic policies. This can be combined with strategic AI investments to achieve both technological innovation and workers’ inclusion.