Key Takeaways

- South-East Asia’s market integration is set to deepen over the next five years even as uneven implementation poses regulatory hurdles.

- Growing infrastructure, energy and industrial investment across South-East Asia is opening significant opportunities for Australian companies, especially in consulting and engineering, though political risks persist.

- Increasing infrastructure, energy and industrial expenditure is supporting ongoing but fragile middle-class expansion and raising demand for Australian services and consumer goods.

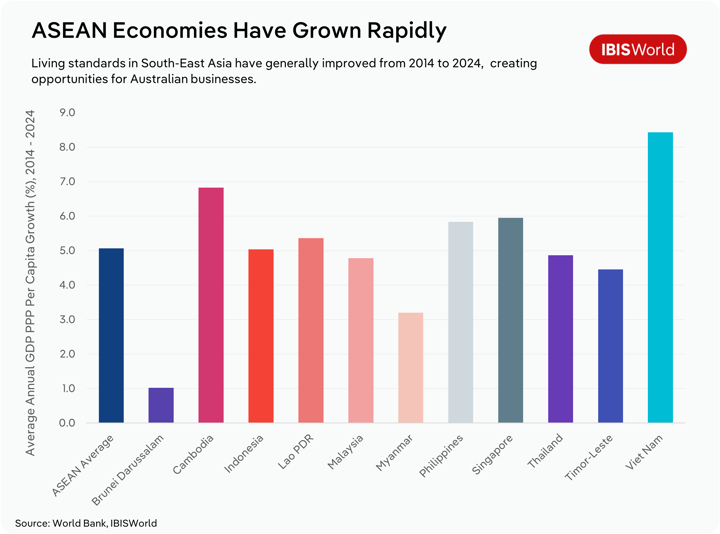

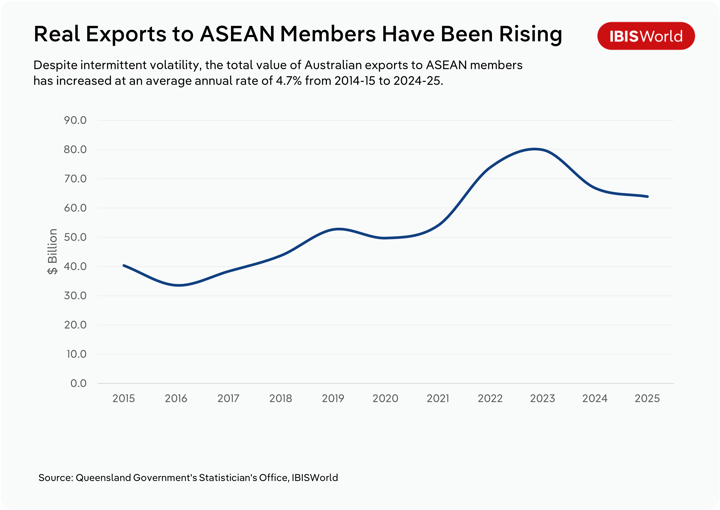

Over the last four decades, South‑East Asia has experienced significant economic transformation. Despite occasional setbacks like the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997, this sustained momentum has positioned the region as a critical hub for global trade and investment. In 2024, the 10 Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) member states at the time brought in approximately US$3.8 trillion in merchandise trade flows and attracted over US$226.0 billion in Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). ASEAN’s share of global FDI flows has expanded from around 6% in the mid-2000s to more than 17% by 2023, showing resilient growth even in times when global FDI volumes fell. Given the region’s dynamic and diverse economic, social and political landscape, Australian companies interested in expanding to South-East Asian markets need to closely monitor key trends over the next five years, as these will shape investment opportunities and risks.

ASEAN is moving towards a more integrated market

As outlined in the ASEAN Economic Community Strategic Plan 2026–2030, a push towards greater market integration reflects longstanding ambitions to boost regional economic growth through deeper multilateral ties. Recent key movements towards market integration include the upgraded ASEAN Trade in Goods Agreement (ATIGA), the Digital Economy Framework Agreement (DEFA) and the ASEAN Plan of Action for Energy Cooperation (APAEC) 2026-2030.

Upgraded ASEAN Trade in Goods Agreement (ATIGA)

Since 2010, ATIGA has underpinned trade among ASEAN members, cutting both tariff and non-tariff barriers for over 98% of goods since its enactment and establishing a framework for consistent customs rules and procedures.

The upgraded ATIGA, formally known as the Second Protocol to Amend the ASEAN Trade in Goods Agreement, was signed in October 2025. It extends tariff‑free access to around 99% of goods traded among ASEAN members and nearly eliminates remaining intra‑regional tariffs. While the agreement’s full text hasn’t been released as at January 2026, it broadly aims to tighten discipline on non‑tariff barriers and streamline rules of origin and customs procedures. It also includes provisions for sustainability and trade in circular-economy goods.

Given that the remaining 1% of goods comprises specific agricultural goods and automotive parts, the expansion of tariff-free trade won’t radically reshape markets. Nonetheless, tighter alignment on trade rules and customs procedures and more decisive action on eliminating non‑tariff barriers will potentially increase intra-regional trade.

The upgraded ATIGA, along with the recently ratified ASEAN Trade in Goods Agreement and the ASEAN-Australia-New Zealand Free Trade Area Upgrade effective from April 2025, creates a more consistent framework for Australian exporters and investors, improving market access and trade across the region. This results in more straightforward procedures across the region, making it easier for Australian businesses to develop regional supply chains or serve consumers from a central hub.

The Digital Economy Framework Agreement (DEFA)

The DEFA expedites regional regulatory alignment on key digital issues like ecommerce, electronic payment systems, AI, privacy, cybersecurity and other emerging technologies, which is currently patchy. ASEAN is scheduled to sign the DEFA in 2026, after two years of negotiations concluded in October 2025.

Once enacted, the DEFA will create a more integrated digital marketplace, boosting the region’s digital economy close to a projected US$2 trillion by 2030. By harmonising rules on data flows, ecommerce, digital payments and cybersecurity, DEFA is expected to create a more uniform regulatory environment for Australian firms in digital services, software development and ecommerce to easily expand their services across South-East Asian jurisdictions.

ASEAN Plan of Action for Energy Cooperation (APAEC) 2026–2030

Signed in October 2025, the APAEC will drive deeper collaboration on energy policy and decarbonisation. Like the upgraded ATIGA and the forthcoming DEFA, it endeavours to harmonise regulations across nations in areas like cross‑border power trading, transmission infrastructure and renewable‑energy investing. Crucially, the agreement sets targets for renewables to supply 30% of ASEAN members’ primary energy mix and 45% of installed power generation capacity by 2030, supporting a 40% reduction in total energy intensity compared with 2005 levels.

APAEC’s provisions will contribute to energy security by diversifying electricity supply and reducing exposure to external energy shocks. Stronger infrastructure connectivity will enable countries to seamlessly trade surplus energy, optimise generation assets and better manage capacity constraints. This gives Australian energy and infrastructure firms, like those with expertise in grid planning and storage and system integration, an opportunity to partner on regional projects. Similarly, Australian developers could support large‑scale renewable and transmission projects through blended finance and advisory services.

Risks from ASEAN market integration

Australian businesses should be mindful that ASEAN agreements will be implemented unevenly, as some countries face domestic political constraints, poor financial resources and bureaucratic inefficiencies. This is especially relevant for DEFA and APAEC, given that executing these agreements will hinge on complex long‑term digital and energy infrastructure investments.

Countries like Singapore and Malaysia are likely to remain early movers on new commitments, reflecting their stronger institutions, high‑quality infrastructure and already-deep integration into regional digital and energy markets. Australian firms can use these leaders as entry points, basing themselves in hubs like Kuala Lumpur to trial regulatory frameworks and develop regional offerings.

This approach allows companies to prepare for expansion into riskier markets as regulatory barriers across the region gradually ease. For example, lower‑income members like Cambodia and Laos are likely to face greater administrative and financing constraints, delaying their ability to fully implement these principles. This disparity makes it important for Australian investors to double down on compliance and develop the expertise needed to navigate evolving rules for goods, digital services and energy across ASEAN jurisdictions.

ASEAN states are investing in infrastructure, energy and industrial policy

In line with intensifying regional and global economic integration, and to support further economic growth, ASEAN members are set to ramp up investment in transport infrastructure. Indonesia, for example, is expanding its national transport network by adding over 2,400 kilometres of toll roads by 2029 and improving public transport between major cities. The Philippines, similarly, has lined up investments in railway infrastructure, including projects like the North-South Commuter Rail in Luzon, which is expected to be fully operational by the early 2030s. Aside from transport infrastructure, the region is also making strides in energy projects, like Malaysia’s Southern Johor Renewable Energy Corridor; a roughly 2,000‑square‑kilometre zone dedicated to large‑scale solar and battery energy storage.

A number of ASEAN countries are also advancing their industrial policies to move up the value chain. Vietnam has set out its industrial roadmap through 2030 under Resolution 23-NQ/TW, with the latter half of the 2020s dedicated to scaling state investment in technological sectors like electronics and electric vehicles, as well as expanding industrial and high‑tech parks. Similarly, Indonesia is expanding export controls to build its critical minerals processing sector and capture value in global renewable energy and electric vehicle supply chains. Indonesia will also be channelling substantial government investment and tax incentives into various manufacturing industries through 2030 as part of its Making Indonesia 4.0 plan.

Elevated investments in infrastructure, energy and industrial policy open opportunities for Australian firms operating in consulting, management, engineering and utilities to get involved in major projects. Governments in the region will look to international private firms with strong portfolios for support, especially as these projects increasingly demand sophisticated engineering technology and skills. At the same time, Australian mining companies will be increasingly well placed to support South‑East Asia’s infrastructure drive and advanced manufacturing supply chains.

Middle-class growth

These investment patterns are driving major structural changes and expanding the middle class throughout South-East Asia. As transport and digital networks improve, businesses benefit from lower logistics costs, increased production and improved cross-border value chains. Likewise, access to clean and reliable energy supports advanced manufacturing and modern services sectors. Targeted industrial policies further this development by directing investment into key sectors, creating higher-paid jobs and expanding governments’ capacity to fund future productive infrastructure.

Greater investment in the workforce will be key to nurturing high-tech industries like semiconductor manufacturing. For example, in November 2025, the Vietnamese Ministry of Education and Training earmarked approximately US$23 billion for investments through 2035, with an emphasis on STEM and English education. A regional push to upgrade labour forces will support more advanced industries, but also contribute to an expanding high-income, well-educated urban middle-class across the region.

Australian companies in education and training, as well as professional and technical services, will have an opportunity to advance South-East Asia’s workforce over the coming years, helping workers move into higher-income jobs by delivering skills in areas like engineering, management, digital technologies and English. Growing demand is creating expansion opportunities for Australian education providers already operating in the region. For instance, Monash University Malaysia has announced a $1 billion new Kuala Lumpur campus to accommodate increased demand, with the project expected to be completed by 2032.

As the region’s middle-class grows and household incomes rise, consumers will seek out a greater variety of imported food, drinks and household products, benefiting Australian exporters. The Australian Government reported sending over 23% of the nation’s agricultural, fisheries and forestry exports to ASEAN members in 2022-23, totalling around $19 billion. This includes key products like beef, sheep meat and dairy, which will see higher consumption as average discretionary spending grows across the region.

Risks from government spending patterns

While swelling investment in infrastructure and energy may appear promising for Australian firms, they should approach major project partnerships with caution. Government corruption in some ASEAN countries remains a threat to projects’ completion, with risks ranging from opaque procurement rules that favour domestic suppliers to misallocated funds and politically driven project changes. The recent 2025 flood‑control projects scandal in the Philippines, where extensive allegations of monopolised contracts and incomplete works have emerged, illustrates how inadequate planning and weak oversight can fatally undermine projects.

Australian companies seeking to participate in major projects should invest in compliance departments and prioritise projects that sit within robust international safeguard frameworks. Projects financed or co‑financed by global institutions like the Asian Development Bank typically apply stricter rules on procurement, environmental and social safeguards and financial management, which reduces the likelihood of corrupt practices. Moreover, Australian companies should prioritise local partners with proven track records of working with foreign investors and multinational companies, as this experience often indicates familiarity with international standards like those reflected in the UN Convention Against Corruption.

Middle-class growth is not a given

An excessive state focus on infrastructure, energy and industrial policy can leave many other public services strained, especially in areas like health and social protection, deepening inequality among low‑ and middle‑income households. The widespread Dark Indonesia protests in 2025 highlight how precarious middle‑class gains can be in South‑East Asia. In these demonstrations, Indonesians mobilised around cost‑of‑living pressures, corruption, subsidy reforms and broader austerity measures.

For Australian companies, fragile middle-class growth means that demand for Australian goods and services purchased with discretionary income can fluctuate quickly. In periods of rising living costs, political instability or cuts to social spending, households may delay or forgo discretionary purchases, eroding previously projected export or investment opportunities.

Given the demographic’s vulnerability, Australian companies should focus on product segmentation and localised formats, tailoring product sizes, pricepoints and features to different income tiers so that demand remains even when household budgets tighten. Australian companies can also gather insights from local partners and customers to respond quickly to changing preferences and expectations, enabling them to adapt their products, marketing and pricing strategies to evolving consumer needs.

Final Word

As South-East Asia becomes more integrated and state investments in infrastructure, energy and industrial policy expand, Australian companies have a wealth of opportunities to tap into robust economic growth and gain access to attractive markets. However, these opportunities come with challenges like market integration frictions and political risks, including inconsistent regulatory enforcement and corruption. This means Australian businesses need to remain proactive with compliance across diverse jurisdictions and an evolving regulatory landscape.

Australian companies targeting consumers should be aware that while the middle-class market is expanding, it remains sensitive to economic pressures and policy changes. To ensure they’re well placed to adapt to shifts in demand, Australian firms should maintain a close watch on local conditions and keep their strategies flexible.